HOME » BLOG » AUTISM AND SELF INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR

AUTISM AND SELF INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR

I’M AN AUTISTIC ADULT AND I EXPERIENCE SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIORS.

When I was a child and later a teenager, I had frequent meltdowns. There were phases during which I had daily meltdowns, often multiple meltdowns a day. Those were the times of being an undiagnosed, unsupported, unaccommodated autistic youth.

I frequently self-injured during my meltdowns. I thrashed my limbs about and smashed them into walls and furniture. I hit myself, bit myself, scratched myself, and hit my head against the wall.

Anyone who ever witnessed any of my “outbursts” just wanted me to stop.

And that’s what they tried to get me to do: Stop that disturbing behavior.

The thing was: I couldn’t.

Because this self-injurious behavior wasn’t something I did.

It was something that happened to me.

Other people always thought that the self-injurious behavior was the problem.

That to “fix” me, they had to get me to “stop doing that”.

They were wrong.

The self-injurious behavior wasn’t the problem.

The self-injurious behavior was a result of the problem.

The underlying problem caused the self-injurious behavior.

Today, I am an adult who is diagnosed as autistic, has learned a lot about being autistic, knows themselves and their autistic traits and needs well, and has many supports and accommodations in place – but what was true for me in my youth is still true today:

THE SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR IS NOT THE PROBLEM.

WHAT CAUSES THE SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR IS THE PROBLEM.

This bears repeating:

The self-injurious behavior is not the problem.

What causes the self-injurious behavior is the problem.

That doesn’t mean that self-injurious behavior is never harmful, dangerous, or in need of support.

It means that the point of approach to minimize self-injurious behaviors is not the self-injurious behavior itself but what causes it.

It’s important to understand that self-injurious behavior is an involuntary reaction to a trigger. It’s not intentional self-harming. Additionally, the amount of control a person has to willingly stop their self-injurious behavior varies greatly. It varies greatly among individuals as well as for each individual among different situations, triggers, and circumstances. Thus, don’t expect or demand control.

TO MINIMIZE SELF-INJURIOUS BEHAVIOR, MINIMIZE ITS TRIGGERS.

Whether you experience self-injurious behavior yourself, or are someone without lived experience who wants to support someone who self-injures – the key is understanding.

There is always a cause for self-injurious behavior. Always.

And that cause is not autism.

Self-injurious behavior is not an autistic trait.

Being autistic doesn’t make people experience self-injurious behavior.

Far too often, I witness people who treat self-injurious behavior as inevitable, as just a part of a person’s autism. This often results in not addressing the underlying cause but only reacting to the self-injurious behavior – by just putting protective gear on people, using restraint, institutionalizing people, drugging people to sedate them, and so on and so forth.

To only address the self-injurious behavior but not its cause leads to autistic people going their entire lives experiencing self-injurious behaviors and their causes unnecessarily. It also leads to horrific health outcomes for many autistic people – not just from the self-injurious behaviors themselves, but also because frequently the underlying cause for self-injurious behaviors are health-related. If underlying health problems aren’t addressed, they commonly worsen.

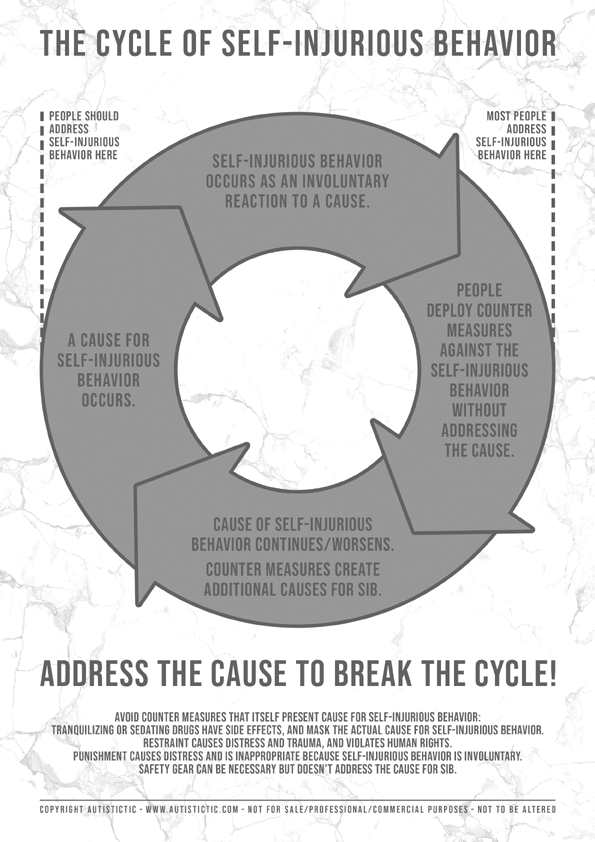

To address self-injurious behaviors, but not their causes often leads to a vicious, worsening cycle:

1. Something causes self-injurious behavior.

2. People only react to the self-injurious behavior, the cause remains unaddressed.

3. The cause remains and often worsens.

4. The self-injurious behavior remains and often worsens along with the worsening cause.

5. More and more frequent and stronger measures are used to address the worsening self-injurious behavior.

6. The autistic person not only suffers from the initial cause of the self-injurious behavior, but now also from the more frequent and stronger counter-measures.

7. The counter-measures cause more self-injurious behavior. Additionally, the original self-injurious behavior remains.

8. Self-injurious behavior caused by counter-measures is misinterpreted just like the original self-injurious behavior.

9. Everything continues getting worse and worse in this cycle because the causes are never recognized and addressed.

Thus, please never forget that self-injurious behavior is just an observable sign of whatever is causing it.

1. Figure out the cause.

2. Address the cause appropriately.

This is simple in theory, but it’s not always simple in practice. That’s because there are so many possible causes for self-injurious behaviors. Understanding and distinguishing them isn’t always easy.

To give you an idea of what may cause self-injurious behaviors, here’s what causes mine – and how to properly support me in each case:

1. MELTDOWNS

My number one cause for severe self-injurious behaviors is meltdowns. To minimize self-injurious behavior for me thus mostly means to minimize meltdowns. That in turn requires understanding and avoiding my meltdown triggers.

For me, I most commonly get overloaded from trying to cognitively process information when I am beyond my capacity threshold. An example of this would be trying to process and fill out a form while beyond capacity.

Support that works for me:

a) Help me do the processing. Share the processing load.

b) Do the processing for me. Take over the processing load.

c) Remind and/or prompt me to take a break, let the overload subside, and come back to it later.

Remind/prompt me later so I can actually get back to it.

d) Remove any dangerous objects from my reach when I do get a meltdown.

e) Take safe-keeping measures (e.g. put a pillow between my head and the wall).

f) Offer/hand me/put protective equipment on me (e.g. boxing gloves, epilepsy helmet)

g) Do not>/strong> try to touch or worse restrain me.

h) Do not try to talk to me, ask me questions, demand things from me, etc.

2. ONE-OFF TRIGGERS

I sometimes self-injure briefly as an involuntary, automatic reaction to spontaneous, individual triggers. Jump scares are a common trigger for me. Sudden, unexpected loud noises or touch are another.

Support that works for me:

a) Avoid known triggers.

b) Just let me self-injure briefly if it happens. It’s over quickly, usually in a couple of seconds, and trying to stop me causes way more problems than a brief bout of self-injurious behavior.

3. ONGOING TRIGGERS

I sometimes self-injure due to distress I experience from ongoing sensory triggers – like when people are having a party outside and the noise is unbearable for me.

Support that works for me:

a) Avoid known triggers.

b) Remove triggers that were unavoidable.

c) Use sensory accommodations.

d) Remind/prompt me to use sensory accommodations.

e) Use my known coping measures.

f) Remind/prompt me to use my known coping measures.

e) If nothing works, let me self-injure. If it gets severe, use my agreed-upon safe-keeping measures.

4. COMMUNICATION ISSUES

Sometimes communication frustration causes me self-injurious behavior.

Support that works for me:

a) Offer me my AAC device.

b) Remind/prompt me of alternative communication like pointing.

c) Offer to guess what I’m trying to communicate.

d) Remind me that I can take a break and try again later.

e) Offer to communicate for me when I’m trying to communicate with a third party.

f) If nothing works, let me self-injure. If it gets severe, use my agreed-upon safe-keeping measures.

5. SELF-REGULATION

I sometimes self-injure because I am distressed, anxious, nervous, excited, in pain – in short experience something big emotionally and/or physically.

Support that works for me:

a) Don’t comment on my self-injurious behavior.

b) If you have an idea how to mitigate the cause, suggest that.

c) If I don’t react, decline your offer, or there is no way to mitigate, let me continue.

I need the input to self-regulate.

c) Usually my self-regulation self-injurious behavior is not severe.

If it gets severe, use my agreed-upon safe-keeping measures.

After a bout of self-injurious behavior is over, I appreciate the offer and possible follow-through to help me with my recovery. This may include things like helping me dress my wounds, getting me ice for my injuries, giving me painkillers, and taking me to a doctor or the hospital if required.

It also includes things like bringing me some food and/or drink, helping me find a comfortable place to settle down to rest awhile, and helping me set up something that helps me to recover like my favorite movie or TV show.

PRIORITIZING THE SELF-INJURING PERSON’S NEEDS

Whenever I witness discussions about self-injurious behavior, people who don’t experience it virtually unanimously agree: it’s bad and should be stopped.

As someone who has experienced SIB all their life and still does to this day, let me tell you this:

It shouldn’t be outside observers of self-injurious behaviors who get to determine when a SIB is bad and should be stopped. It should be up to the person experiencing the SIB.

I understand that witnessing self-injurious behaviors can be difficult, uncomfortable, and scary.

The closer you are to the self-injuring person, the more you love them, the harder it can be.

That is valid. But it doesn’t trump the self-injuring person’s needs or human rights.

Please listen to the self-injuring person instead of just projecting your own opinion, thoughts, wants, and needs onto them.

RETHINK THE CONCEPT OF “DANGEROUS”

Whenever I witness discussions about self-injurious behaviors, the word “dangerous” gets thrown around constantly. Self-injurious behavior is always “dangerous” when unaffected people discuss it.

I question the concept of “dangerous” in this context because “dangerous” gets applied equally to self-injurious behaviors from lightly pinching one’s skin, over biting and scratching without breaking skin, over giving oneself bruises from hitting, all the way to severe headbanging that causes concussions or wounds that require stitching.

Yes, truly dangerous self-injurious behaviors do exist and they may require safe-keeping measures to be taken.

Headbanging so hard that it causes a concussion is dangerous.

Punching oneself so hard that it causes a wound that needs stitches is dangerous.

Biting one’s own tongue off is dangerous.

But…

Biting one’s hand without breaking skin is not “dangerous”.

Scratching one’s arms and leaving shallow, bloody marks is not “dangerous”.

Bruising one’s hand on a wall without any sprains or broken bones is not “dangerous”.

“Dangerous” is too often used by unaffected people to justify overwriting affected people’s human rights to autonomy, agency, and informed consent.

“Dangerous” is too often used when really the SIB isn’t factually dangerous at all – it just makes people who witness it uncomfortable. They don’t understand it. They find it disturbing and disturbed. They consider it bad. They think it must be stopped.

Please don’t call all SIB “dangerous” unanimously, and/or declare it a problem just so you can justify trying to stop or even punish it.

DIFFICULTIES DON’T JUSTIFY CIRCUMVENTING HUMAN RIGHTS

Many autistic people have communication differences that can make communicating about their self-injurious behaviors difficult. Sadly, this is often used as justification for mistreatment for self-injurious behaviors.

Just because communicating with someone about their self-injurious behaviors is difficult doesn’t mean their human rights can just be circumvented. You have to try. Every time. Again and again.

You have got to respect the self-injuring person as a full and complete human being, equal to yourself.

Work to find methods to communicate with us that work, so you can get our input on our self-injurious behaviors as well as on safe-keeping measures and ways to support us. If one way to communicate doesn’t work, try another. And don’t stop trying until something works. It doesn’t have to be complex, complicated, eloquent, verbal, oral communication.

SAY NO TO PUNISHMENT AND RESTRAINT

Don’t punish self-injurious behavior.

Don’t medicate people for self-injurious behavior. Yes, medication that calms or sedates people can minimize self-injurious behavior. But it doesn’t fix the underlying cause. This means that outside observers don’t have to deal with self-injurious behavior anymore, but the autistic person continues to suffer unseen. The autistic person may well suffer additional negative outcomes from being drugged, as well as from the unaddressed and likely worsening original cause of the self-injurious behavior.

Don’t restrain people for self-injurious behavior, unless their life is in danger and you really don’t have any other option. If you ever have to restrain somebody because you have no other option, make sure you have another option the next time.

Restraint is not an acceptable go-to measure for managing self-injurious behaviors unless the self-injuring person chooses voluntary restraint as one of their agreed-upon safe-keeping measures. In this case, make sure to re-affirm this choice every time and don’t just assume that you get to restrain the person at your own whim.

For me, the most important part of supporting me appropriately as an autistic adult who experiences self-injurious behaviors, is to respect, protect, and affirm my needs and rights: autonomy, including bodily autonomy, agency, and informed consent.

And don’t treat people as less than because they experience self-injurious behavior!

Leave a Reply